|

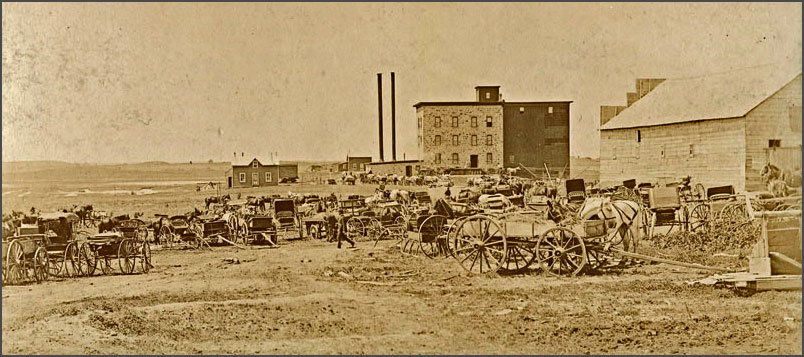

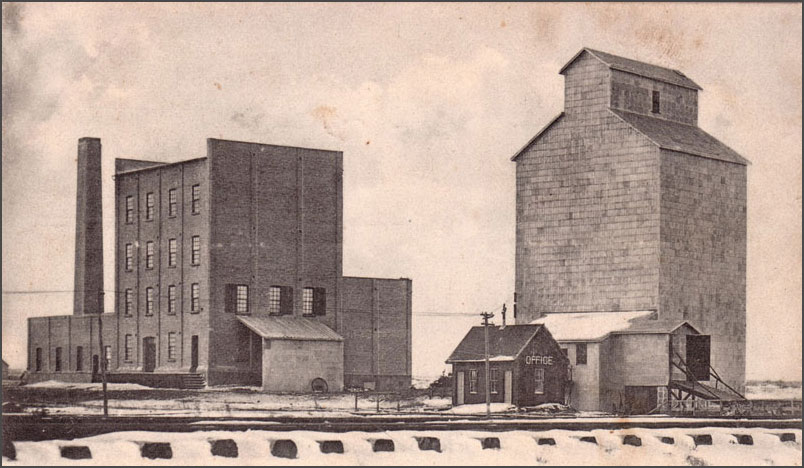

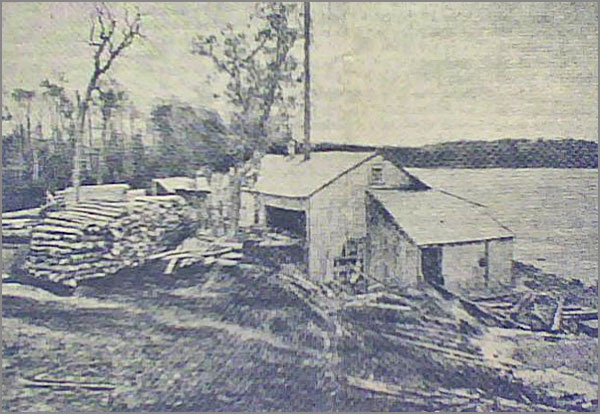

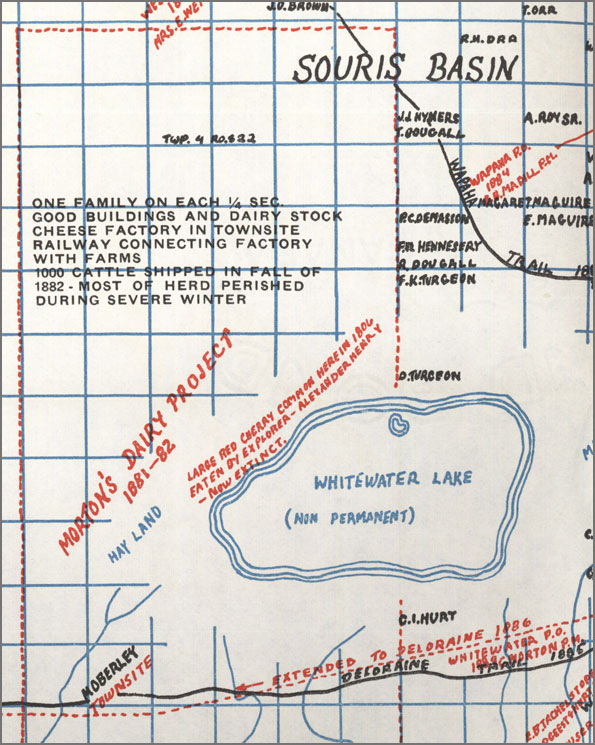

Railway Towns / Boissevain The story of milling in Boissevain begins shortly after the town was established as an important commercial centre on the new CPR line. In those days a progressive town needed a mill. In fact, smaller communities would often offer a “Mill Bonus” of several thousand dollars as an incentive to get one started. In 1889 Preston and McKay built a substantial structure of local sandstone on the west side of Mill Road just south of the CPR track. It housed the latest in mill technology; steel rollers rather than the large millstones, and a steam engine, which replaced reliance on waterpower.  The Preston / McKay Mill 1889 - 1902. Through the frequent downturns of the agricultural economy, a farmer could now at least use a portion of his crop to help feed his family by convert- ing wheat to flour. The mill kept a share of the grist and no money needed to change hands. The mill was soon also exporting flour. In 1894 four carloads were sent to Liverpool, England, and total pro- duction was 400 sacks per day. The First Fire In 1902, when the operation was consumed by fire there was no hesitation. By May of 1905 the Turtle Mountain Milling Co. Ltd., a consortium of local businessmen, had purchased the site and was beginning to erect a new building. By March of 1906, the new mill was in operation. This one had an electric generating plant, which also supplied the first electricity for a few businesses and the town’s street lights.  Turtle Mountain Milling Co. Boissevain: 1906 – 1925. But changes in commerce and transportation began to take effect, and after a few years, business declined. The mill had ceased operations when the onset of World War I revived it. Flour was urgently required for the war effort and a retired miller, George Dow, soon had the mill up and running again – with its entire production of 600 bags per day being shipped over- seas. This wartime use of Boissevain flour created a peacetime market and after 1918 most of the flour still went to England, Scotland, and Holland. The reprieve was short-lived how- ever, and by the 1920’s a network of roads was creating even stronger connections to urban centres. The second mill was still thriving when fire struck it down, but the writing was on the wall. Sources: Boissevain History Book Committee. Beckoning Hills Revisited. “Ours is a Goodly Heritage” Morton – Boissevain 1881 – 1981. Altona. Friesen Printing, 1981. Photos: Boissevain Community Archives. P64 A1, P69 A32 Natural Foods Miller George Dow may have an- ticipated today’s concern with the åœadditives and methods employed in modern food processing. He was an early advocate for un- bleached flour, believing that the bleaching process was harmful in that it removed the wheat germ oil. Although there was a strong demand for bleached flour locally, the government required that all flour for overseas should be un- bleached. Several chemicals used for bleaching have now been banned by the government as dangerous to our health. The Boissevain Roller Mills Building The main building is 30x40, 50 ft. high from the basement, built of stone, with cut stone corners, arches and sills. The engine room is also of stone, 20x30, finished off in the same manner as the main building. Both buildings are roofed with tin. The building cost over $5,000, and is said to be one of the finest mill buildings in Manitoba. The basement of the mill is 11ft. high, and is excavated about three feet, the other eight is above ground. It is largely used for bran, flour and wheat storage and contains the boots of the elevators, the line shafting for driving the rolls, and scouring machine. The grinding floor, also 11 ft. high, contains five double sets of Allis rolls 9x24 and 9x30, a wheat separator, power packer, chop roll and scales. Next is the purifier floor, on which are their Smith purifiers, one Richmond shorts duster, two gravity scalpers and three cyclone dust collectors. The wheat and flour bins are on this floor, the stone walls being lined with ceiling to protect the wheat from frost and damp. The next floor, called the rolling floor, 18 ft. high, contains ten No. 1 George T. Smith Centrifugal Reels and Inter. Elevator bolts, one Eureka Horizontal Scourer, the elevator line and heads, etc…. A Brown automatic cut off engine runs the 125 barrel mill without a tremor or jar. From--- S.Kerry M. Abel, Morton-Boissevain Planning District Heritage Report, District Planning Study, November 1984, HRB, pp. 121-129, with sources. Some notes from the Northwest Farmer.. S: Commercial, April 20, 1886, p. 609. “The residents of Boissevain are raising a bonus to assist in the erection of a roller flour mill at that place.” S: Nwfmm, April 1889, p. 100. “The prospects for a mill at Boissevain, Man. Are good. The people have subscribed $1,500, Deloraine municipality gives $2,000, and it is expected to raise between $5,000 and $6,000 altogether.” S: Nwfmm, June 1889, p. 162. “Preston, of Stradford, Ont., will erect a 100 bbls. Roller mill at Boissevain, Man. It will be stone, 30 x 48, 40 ft. high.” S: Nwfm, December 1889, p. 340. “On recently leaving Stratford, On., to take charge of his mill at Boissevain, Man., Wm. Preston was presented with an address and purse. S: Nwfm, May 1890, p. . Sawmills The Fox Sawmill In 1880 the Fox family acme to the Wakopa area. Thomas and his oldest son Alfred set up a sawmill two miles northeast of Lake Max. People came from many miles around to use the lumber that was produced from this mill. In 1881 Tom decided to take a homestead nearby and settled (on 10-2-19) several miles west of Wakopa in the Adelpha area. In 1884 Tom moved his sawmill west where it was used to cut lumber for the growing CPR. The mill was dismantled and hauled to Brandon where it was shipped to Calgary. Tom went along with his mill while his family stayed behind and his son Frank took over the homestead. Private Operations It was not uncommon for a farmer to own a small portable mill. Such operations continue to this day. In the Mountainside area, Sam Smith had a steam sawmill operating In the fall of 1882. Mr. Morton's Mill: Max Lake / McKinney / Conroy Sawmill. The Max Lake Sawmill also known as the Bolton Sawmill, it was built on Lake Max in 1881. It was bought by George Morton, then later owned by Hugh McCorquodale and then Bill Harvey. Then in 1910 Fred McKinney decided to buy the mill for him and his sons Doug, Bill, and Elson to run. They ran the mill till 1968. There are stories of men from all over going to the mill to get wood, men willing to go through days of travel and fighting a battle with the furiously cold weather. There was a bunk house where they could stay at night with a fireplace in the middle to keep it warm. The mill sat on the northern end of the lake, just west of a stream that flowed into the lake from a slough a couple hundred metres back from the shore. Cut logs were dumped into this slough. Afterwards, they were sent down a man-made channel to the lake where they were chained at the entrance to the lake from the stream. They were held here until there was room in the mill for them to be cut. The mill's boiler stack was guyed up to a majestic oak tree by a long bolt that went straight through the tree.  The sawmill on the edge of north shore of Lake Max, while it was owned by Mr. Morton. The machinery included a planer and shingle-mill. In about 1910 Harvey sold the sawmill to Fred McKinney, who moved it from Lake Max two miles north to his property. They used the mill to do a limited amount of custom sawing until the timber reserve was opened up again in 1930. Bill Eaket soon joined in the operation, lending the use of his gas-powered tractor to run the mill. Everything except for the actual sawing of the lumber was up to the customer to do. Trees were felled (by hand), trimmed and hauled (by horse) to the mill where they were sawed. The cost of this service was $10 to $12 per 1000 board feet. The sawmill generated copious amounts of sawdust, which was put to use by the Municipality of Morton during the early 1930s. After being hauled to town the sawdust was mixed with arsenic and molasses and churned in a small cement mixer. This mixture was then spread along the road allowances to kill grasshoppers. In 1938 Bill Eaket dropped out of the operation and Bill and Doug took over the business from their father. They ran the mill for an additional 25 years. During this time they were mostly sawing for local farmers who needed lumber to construct buildings, corrals and hay shelters. The Morton Dairy The most notable effort however was much more than that. George Morton was dreaming big when he purchased a large tract of land north of Whitewater Lake. He had his eye on a national market. He came with the right experience. He had earned the title Cheese King of Canada while working as a cheese factory owner in Kingston, Ontario. When he came to the Turtle Mountain area in 1878 he saw the potential for large-scale cheese production in this the rich hay land that borders the shoreline of the lake.  Map from Beckoning Hills He persuaded businessmen in Kingston to invest in the Morton Dairy Farm Company and received (via his business connections with John A. MacDonald) the right to purchase 72 square miles (184 kms2) of land west of Whitewater Lake. He also received a confirmation from the CPR that a railway would be built through his land. Each settler involved in the venture occupied one-quarter section of land with a small herd of dairy cattle supplied by the company. Morton bought the Lake Max Sawmill already in operation to supply lumber for his settlers, and he laid out a townsite on the northwest corner of Whitewater Lake to become a business centre and community base. It seemed that everything was in readiness and the venture was destined for success. There were two problems. He wasn’t the only investor to have made plans on the basis of the promise of a rail connection. The railway wasn't built past Whitewater Lake until 1886, and then farther south than Morton had been told, missing his land by a few miles. And then there was the weather. Raising cattle through the vicious winter was trickier than expected. During the summer of 1882, dairy colonists brought 1,000 head of cattle from Emerson and Brandon and built corrals walled with tightly packed swamp hay, open to the sky. During the winter, instead of being let out to generate heat by movement, the cows were tightly packed in their corrals. As the sub-zero temperatures and storms of a prairie winter set in, hundreds of cows froze where they stood. Such a heavy loss ended the cheese project, but Morton had not lost faith in the agricultural potential of the area. He pressed on with his other enterprises and is now recognized of course as the founding father of Boissevain – Morton. Carriage Maker In Boissevain, Butler and Frith were carriage-makers and blacksmiths; Lime Kilns Angus McRuer describes one located near his Desford-area farm… “This kiln was on a rise of land sloped to the north. A hole eight feet deep by ten feet across was made at the top of the slope. A trench three feet wide by thirty feet long was dug, starting at the bottom of the hill, up into the bottom of the big hole. It was like a big clay pipe. The trench acted as a damper.” To prepare for a burn, stones were placed in the kiln leaving an arch at the bottom to hold the fire. The process took three days to reduce the limestone to powder. In addition to using it for making mortar, people used it to purify and freshen damp basements, and in cement and plaster and for whitewashing walls and ceilings. There were several of these small local enterprises in our region. Many are small and barely recognizable. They are usually on the side of a creek bed or hill to allow access to one side of the kiln to feed the fire and to provide the necessary draft to create a hot and steady burn. In the Beckoning Hills account of the history of the Johnstone family we learn that: “He built a log house, a log stable for his oxen and a dugout. Later he had a lime kiln on the bank of the creek where he slacked lime to white wash his house and those of his neighbors. “ Local histories give us glimpses of several sites… “At one time there was a lime kiln on the southeast corner of the Hicks homestead one mile south of the Ninga Cemetery. There was no building. It was just a stone structure set into the side of the hill, about eight feet deep and ten feet in diameter. Limestone was plentiful in the surrounding area. Once it was started, the fire in the kiln was kept going day and night. Wood was used for fuel. Once the man responsible for keeping the fire stoked got drunk and let the fire go out. That batch of lime was spoiled! The intense heat reduced the limestone to powder.” Concrete Block Construction  At

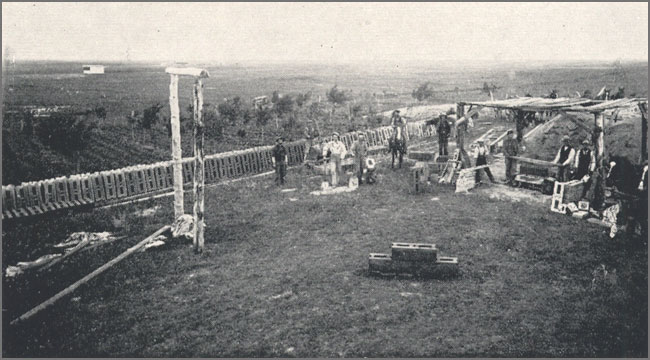

first glance this attractive house on a farm near Boissevain looks

like it might be one of the many fieldstone homes in the region. A

closer look tells us that those building blocks are concrete.

For a few years in the early 20th century, many buildings in southern Manitoba were built with locally cast concrete blocks. Much larger than bricks, the blocks were hollow, and were typically flat on the interior face but variously patterned on the exterior face. Because these blocks did not require high-temperature firing like bricks, there was no need for the substantial infrastructure used in conventional brick-making. They could be made on the building site with portable equipment.  Cement Block Manufacturing on the farm of W.J. McKinney, 1904 – Photo courtesy Mrs. Ina McKinney Beckoning Hills, page 73. |